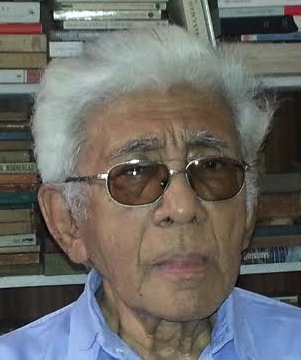

Izeth Hussain

The French have a saying that

goes, "The more it changes, the more it’s the same thing". I wrote an

article many years ago characterizing our Sinhalese-Tamil ethnic problem as an

imbroglio, having in mind the fact that the same problem was going on and on

while the apparent changes were only of a superficial order. The term

"imbroglio" has been in fairly wide usage in recent years, obviously

because it is apposite for a problem that remains unchanged whatever other

changes take place. The enormous change of a war, a thirty –year war, took place,

followed by the even more enormous change of a decisive and definitive defeat

for the LTTE, which led to sanguine expectations of an early solution to the

ethnic problem. But it continues all the same.

However it is a fact – which

is surely well attested by History – that change also takes place. The

following question arises: How do we bring about a change in the ethnic

problem? The dictionary definition of the term "imbroglio" could help

at this point. It means "a confused heap; complicated (especially

political or dramatic) situation". This suggests that a problem continues

without change and without a solution because it has been too confusing to be

understood with all its complications. It suggests further that the way to

approach an imbroglio is to try to get at the fundamentals underlying all the

confusion and the complications.

At this point we have to face

up to a problem. My fundamentals may not be your fundamentals, and what are

recognized by the Tamils as fundamentals, as givens not requiring any arguments,

may not be recognized at all as fundamentals by the Sinhalese. The following

question arises: who is to act as judge or arbiter in deciding what constitute

the fundamentals of the ethnic problem? As this is not a philosophical question

but one pertaining to the realm of practical politics, our answer has to be a

practical one. My answer is that the international community has to act as

judge or arbiter. At this point some readers may emit a howl of rage and, while

still in a sitting posture, voluntarily rise three feet in the air as Wodehouse

might have put it. Surely everyone who is not an utter nitwit knows full well

that the so-called "international community" is just euphemism for a

gang of powerful countries led mostly by crooks and thugs who specialize in

double standards. But there is also another valid usage of the term

"international community". It refers to the totality of the

membership of the United Nations, the member states who are committed by virtue

of that membership to the norms and values set out in the UN Charter, and also

the Declarations and legally binding Covenants on Human Rights. The most

important fact for our purpose is that in the decades following the

establishment of the UN the international community has been placing more and

more value on human rights and democracy. Our fundamentals will therefore be

judged by their approximation or otherwise to the norms of human rights and

democracy.

I come now to the fundamentals

of the ethnic problem as seen by our Tamils. They claim to be just as

indigenous to the national territory of Sri Lanka as the Sinhalese, having been

here as long or even longer. They had a Jaffna kingdom for centuries, and in

any case they have a well-established area of traditional habitation in the

North-East. They therefore have a homeland, on which basis they claim to be a

national minority and not just another minority like the SL Muslims. On that

basis they claim the right to self-determination that is enshrined in the UN

Charter and other legal instruments of the UN. The right to self-determination

is taken as meaning that they have an inalienable right to set up a separate

state, or failing that to a wide measure of autonomy in accordance with the

principle of internal self-determination. Autonomy, which becomes possible

through devolution of power, is consistent with the essential trend of modern

democracy which is to bring government to the grass roots level of the people.

There is nothing new-fangled

about those Tamil fundamentals which have held sway over the Tamil mind for

many decades, long antedating the Vaddukoddai Resolution of 1975; nor is there

the slightest prospect of their changing. That was made quite apparent by the

overwhelming victory of the TNA at the recent Northern Provincial Council elections.

During the election campaign period there was a screeching hysteria, not only

among the hardliners but also in the mainstream media, over indications that

the TNA still regarded Prabhakaran as a hero and was still hankering for Eelam.

All that left the Tamil people unfazed, because they remained dedicated, along

with the TNA, to the principle of either devolution or outright separation. The

elections showed also that the economic strategy on which the Government has

depended for four years to appease the Tamils – the strategy of massive

expenditure on infrastructure – has been a complete flop. The Tamils remain

dedicated to the fundamentals that I have stated above, which really amount to

an absolute on which no compromise is possible. The absolute is this: the

Tamils want joint rule, and will never be satisfied with Sinhalese rule over

the Tamils.

There is a wide and firmly

established consensus, even a near unanimity, among the Tamils about the

fundamentals of the ethnic problem, but among the Sinhalese there is and there

has always been serious schism about the fundamentals. According to the

prevailing orthodoxy, all the historical claims of the Tamils are tosh and

there is no valid basis for self-determination and devolution. Furthermore the

Sinhalese people – according to the orthodoxy – have never accepted and will

never accept devolution because they know that sooner or later it will lead to

a separate state. This notion is factually incorrect because there is evidence

showing that the Sinhalese people have in the past been prepared to accept a

wide measure of devolution.

However, I am prepared to

acknowledge that at the present stage – whatever may have been the case in the

past – suspicions about the possible ill consequences of devolution are

widespread among the Sinhalese people. Some would hold that even a modest

amount of devolution would lead ineluctably by a linear progression to a

separate state. Others would hold that devolution could conceivably set off

unforeseeable processes that might lead to separation or something close to it.

Either way, it appears that the Sinhalese consensus would be prepared to allow

only a very modest measure of devolution – not 13A + but 13A -, without land

and police powers. There is therefore a stark dichotomy in the Sinhalese and

Tamil understanding of the fundamentals of the ethnic problem: the Tamils claim

the right to a very wide measure of devolution or even separation, while the

Sinhalese could be prepared to allow only a very modest extent of devolution

that will never satisfy the Tamils.

On that reading we have to

expect the ethnic imbroglio to continue. How do we get out of the imbroglio? I

believe that the only way is to show that the Sinhalese fears about the

possible ill consequences of devolution are entirely unfounded. I have in mind

a simple and straightforward argument that I believe cannot be controverted. A

country can break up only for one of two possible reasons: either a government

is willing to allow it, or cannot prevent it. Eritrea, East Timor, and South

Sudan became separate states because the Governments of Ethiopia, Indonesia,

and Sudan were willing to allow that outcome, behind which was probably the

recognition that they never had a legitimate claim to those territories. Kosovo

became a separate state because the Serbs, not being able to withstand NATO

power, could not prevent it. In the case of Sri Lanka, it is impossible to

envisage any Government being willing to relinquish sovereignty over the

North-East on the ground that we never had a legitimate claim to that

territory. Sri Lanka can break up only because of inability to withstand an

external force. The important point is that devolution will never by itself

lead to the breakup of Sri Lanka.

At this point I must pose a

very commomnsensical question: if devolution will lead to separation or promote

it, why was Prabhakaran so adamantly opposed to it? Obviously he was convinced

that devolution would prevent separation, not lead to it. And behind that

conviction he very probably had in mind the pragmatic experience of India in

preventing its breakup. Historically India never was a single political unit,

not even under British rule because during that time about a third of Indian

territory was under the Maharajas. India was fully unified only after 1947, and

the single most important instrument in preserving that unity – a mighty

achievement – was devolution. That was why India imposed 13A on us: devolution

here too seemed the best way of preserving unity.

I have stated above that Sri

Lanka can break up only because of our inability to withstand an external

force. I have written more than one article in the past on the possibility –

only as a worst case hypothesis – that India might impose a Cyprus-style

solution on Sri Lankan. The late H.L. de Silva wrote some months before he

passed away that initially he had found my arguments to be rather fanciful, but

later he came to take them seriously. I will not recapitulate those arguments.

Instead I will now make a point of the highest importance: India has to be

regarded as an integral part of our ethnic problem, indeed as one of its

fundamentals. If not for India’s interest in our Tamils – a perfectly

legitimate interest it must be said – the rest of the world would hardly notice

them. Our Government would have been free to treat them simply as a conquered

people without their being any unwelcome repercussions.

I believe that Indian

intervention in Sri Lanka might take place only under two conditions. One is

that ill treatment of Tamils here causes very serious reactions in Tamil Nadu –

such as for instance the formation of separatist movements. We have to bear in

mind the changing international situation and their possible impact on Sri

Lanka, about which we can never be quite certain. I have in mind for instance

the possible deleterious impact on Indo-Sri Lankan relations of the growing

Chinese presence here. Any way the principle is this: the first condition for

intervention is that India comes to believe that its vital and primordial interests

are being threatened by the ill-treatment of Tamils here. The second condition

is that, not just Tamil Nadu, but the international community comes to believe

that the treatment of our Tamils is morally outrageous and intolerable. As I

have pointed out earlier in this article, the treatment of our Tamils will be

judged by its approximation or otherwise to the norms of human rights and

democracy. I doubt that India will intervene in Sri Lanka unless it believes

that it has the broad backing of the international community.

Is there any way out of the

ethnic imbroglio? There could be if we conceptualize a political solution as

emerging from an organic process of growth rather than through legislation and

the putting in place of certain institutions. I have in mind the opportunities

that might be offered by the Northern Provincial Council. 13A is certainly far

from what the Tamils desire, but much can be done for the Tamils within its

ambit, even in its presently truncated form without police and land powers.

Suppose the TNA makes a success of the NPC? It could come to be emulated by the

other PCs which up to now have been largely useless institutions. But for the

success of the NPC the Government’s co-operation will be required, and – above

all – the racists and the neo-Fascists will have to be kept in check, as they

will find the idea of any Tamil success unbearable.

_____________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________

Izeth Hussain, The

Ethnic Imbroglio, The Island, Colombo, 2013-09-28.

No comments:

Post a Comment